Sustainability is “no longer a moral choice”, it’s an “economic imperative”

Indonesia Business Post

Indonesia balances rapid economic growth with environmental and social consequences of its extractive industries amid growing global awareness of sustainability.

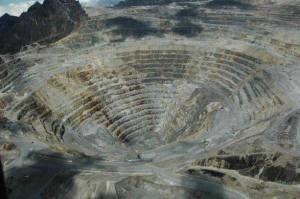

The nickel boom, largely fueled by Chinese investment, has brought not only industrial growth, but also ecological degradation, displacement of indigenous communities, and rising public concern over pollution and floods.

Against this backdrop, Indonesia Business Post sat down with Peter Bakker, President & CEO of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), an international organization that brings together 270 of the world’s leading companies − from Unilever and Nestlé to Toyota and Alibaba − to advance sustainable business practices.

In an interview with Renold Rinaldi, Bakker explains why sustainability must move beyond being a moral debate and become an economic necessity, how businesses can assess physical climate risks in their supply chains, and what opportunities lie ahead for developing nations like Indonesia to lead in regenerative agriculture and nature-based solutions.

How do you assess the current state of corporate sustainability, particularly in emerging economies such as Indonesia?

Over the past decade, we’ve seen remarkable progress. Companies no longer ask why sustainability matters, theyask how fast they can transition. In emerging economies like Indonesia, the conversation is shifting from compliance to competitiveness. Sustainability is becoming a driver of innovation and market access. But challenges remain, particularly around financing the transition and ensuring small and medium enterprises are not left behind.

Indonesia’s industrial expansion, especially in nickel and energy, has raised concerns about their social and environmental impacts. How should companies respond to these tensions?

This is a defining moment. The world needs critical minerals, but how they’re produced will determine whether we meet our global climate goals. Companies operating in extractive sectors must go beyond regulatory compliance. They should invest in ecosystem restoration, fair labor practices, and transparent community engagement. True sustainability means communities living near industrial zones experience progress, not displacement nor pollution.

How do you see global supply chains adapting to climate-related risks?

Physical climate risks are no longer abstract. Floods, heatwaves, and droughts directly disrupt logistics and production. Leading companies are now mapping their exposure to these risks not just at the factory level, but across their entire supply chains. This is where technology and collaboration matter.

We see increasing partnerships between corporations, local governments, and even farmers to build resilience together.

What role can Indonesia play in global sustainability transition?

Indonesia has unique potential. It’s one of the few countries that can be a global leader in both biodiversity protection and renewable energy. From nature-based solutions to sustainable agriculture and blue economy initiatives, Indonesia could redefine what a just and inclusive energy transition looks like. But it will require coherent policy alignment between ministries, business sectors, and local communities.

WBCSD celebrates its 30th anniversary this year. What lessons stand out from three decades of promoting sustainable business?

Perhaps the biggest lesson is that sustainability is no longer a moral choice, it’s an economic imperative.

Companies that fail to adapt will face higher costs, stricter regulation, and reputational risks. But those who act early will find new markets, stronger investor confidence, and long-term profitability. The private sector has the power and responsibility to accelerate change at scale.

Indonesia is trying to balance rapid economic growth with sustainability goals. What key lessons should it take from other countries?

The main lesson is that no single sector can do it alone. You need government, the financial sector, and business to work together to understand not only the risks from climate and biodiversity loss, but also the opportunities.

If we get it right, Indonesia could build a massive carbon market, expand biofuels, and develop other low-carbon solutions. But this requires a policy environment that supports investment, financing mechanisms that de-risk innovation, and companies capable of managing these projects effectively. The outcome could be sustainable growth and stronger integration into global economy.

How can Indonesian companies move beyond being commodity producers and become global leaders in agricultural resilience?

By learning from the best and by being transparent. Companies must be able to conduct carbon and nature accounting, integrate these into their core business decisions and should not treat sustainability as a separate report handled by a small team.

Every company should carry out risk assessments and resilience planning. Larger firms should join international platforms, exchange best practices, and adopt regenerative models. Over time, as you improve and disclose data transparently, markets will reward you with greater access and credibility.

The CEO Handbook on Physical Risk emphasizes resilience as a boardroom priority. What are its main takeaways for Indonesian business leaders?

The handbook tells CEOs that they can’t delegate sustainability. It’s not just the job of a “sustainability officer.” Every function finance, procurement, HR must play a role.

The CFO should lead on risk assessment, procurement should engage suppliers, and HR must train employees on new sustainability standards. The handbook provides key questions each department should ask to start an internal conversation about resilience. Once that dialogue begins, real change follows.

How should companies start measuring and managing climate-related physical risks?

Start by mapping your most material risks, whether it’s flooding, drought, or declining yields. Then, identify what data you already have, what you need to collect, and which parts of your supply chain must contribute.

Next, quantify those risks. For example, calculate how much profit could be lost or how insurance costs might rise if no action is taken. If you can show that doing nothing will erode 25 percent of your profits or leave you uninsurable, you build a solid business case for investing in resilience.

What differentiates companies that are merely compliant from those that are truly resilient?

Resilient companies go beyond compliance, they integrate environmental and social metrics into their profit and loss statements. A great example is Olam Agri, which has developed an integrated P&L covering financial, social, and environmental performance. That’s the “platinum standard.”

It takes years to reach that level, but every company should aim for it. The point is not to impress investors, but to manage the business better. Collect data that’s useful for decisions not just what’s required for reporting.

Where do you see the greatest opportunities for Indonesia to lead in sustainability?

Forestry, agriculture, and energy transition are deeply interconnected. Indonesia’s forests hold immense potential for carbon markets. Agriculture, if made more resilient, strengthens food security. And the waste from both sectors can feed biofuel production linking energy and environmental goals.

Given the new administration’s focus on energy, food, and health security, these agendas align naturally. Clean air, sustainable farming, and renewable energy are not just environmental issues they’re economic ones.

Finally, what message would you deliver to Indonesian CEOs and policymakers?

First, make sustainability an economic conversation. If government, finance, and business collaborate, sustainability can become a competitive advantage − driving innovation, investment, and growth.

Second, focus on resilience. Indonesia’s geography makes it vulnerable to climate risks. Ignoring them will eventually undermine productivity and growth.

The opportunity is enormous, but so are the risks. If Indonesia continues investing heavily in fossil fuels without managing physical risks, climate impacts will “bite back.” But if it leverages its forests, innovation, and private-sector dynamism, it can become a true global leader in sustainable development.

Already have an account? Sign In

-

Start reading

Freemium

-

Monthly Subscription

20% OFF$29.75

$37.19/MonthCancel anytime

This offer is open to all new subscribers!

Subscribe now -

Yearly Subscription

33% OFF$228.13

$340.5/YearCancel anytime

This offer is open to all new subscribers!

Subscribe now